I've found out what the biggest problem (I certainly see it as a problem) with the new GCSEs is.

I don't think it's the content and specifications.

I don't think it's the number of exams students are now sitting.

It's the kids.

Current year 9 and above, maybe beyond, hold a belief that when they got a C they had finished third in a race. I get that. A and A* were the same grade to them, a B is next and a C is finishing third.

Finish third and you now get a 7. That means that those who were happy with a C (finishing 3rd) are now unhappy with a 5 (finishing 5th) or a 6 (finishing 4th).

Kids are sending themselves to the brink of stress and breakdown to achieve things that, in the time they're given, is beyond them. They're aiming for grades 3, 4 or even 5 grades above their FFT20 estimates.

A 4 isn't finishing 6th, it's the same as a good pass from 3 years ago. It's totally acceptable, and anything better is the same as finishing 2nd or 1st three years ago.

I think our young people haven't had this message clearly enough.

That's a huge problem.

Friday, 16 November 2018

Tuesday, 30 October 2018

Breakfast Revision

In the run-in to the GCSE exams in 2018 we invited 23 students to morning revision sessions.

"If you can get to school for 7:45am (we're aware of a large proportion of our students travelling across Leeds or acting as carers to siblings in a morning), a minimum of two members of staff will be available for half an hour every morning to make a difference to your GCSE maths grade."

Unfortunately, nine didn't take us up on the offer at all and three students only attended one day out of the four weeks. Fortunately, word spread and a good number of students asked if they could join us and we ended up with about 10 students every morning for 3-4 weeks.

As part of the provision, we offered breakfast. Toast, specifically. Plate-loads of it - that the students never bothered with, so I ate a lot and so did my year 8 form!

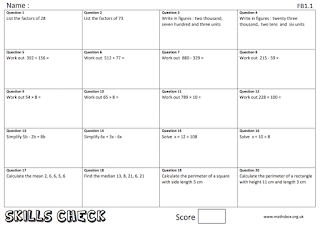

It was really easy to run. We subscribe to Mathsbox.org.uk, so printed a booklet of their Skills Check worksheets. 2 pages from each of sets 1 to 6 at three different levels to suit the needs of the students that we'd invited.

Students came in, were handed theirs and worked through it - asking for help where they needed it and were directed to the same problem on the next sheet to check that they'd taken in what had just been said.

The question is... did it work?

Was it worth rushing in and being there from 7:30 because one student couldn't wait for 7:45?!

I'd like to think so.

Our data suggests so. The average progress made by all students in our Year 11 cohort last year between their second mock exam and their GCSE exam was 0.2 grades. Using the 11 students who achieved for at least a full week, the average progress in the same amount of time 0.4.

Will we be doing this again this year? Absolutely.

We're running it two mornings per week from the first week back after half term - 30 students have been invited with students already asking why they haven't been invited ("It's not that you're not welcome, you definitely are, but we haven't identified a need to tell you that you need to be there.")

I'm hoping two mornings per week is more sustainable over a longer period of time to maintain engagement and progress. It also gives me the opportunity to identify different needs throughout the year.

"If you can get to school for 7:45am (we're aware of a large proportion of our students travelling across Leeds or acting as carers to siblings in a morning), a minimum of two members of staff will be available for half an hour every morning to make a difference to your GCSE maths grade."

Unfortunately, nine didn't take us up on the offer at all and three students only attended one day out of the four weeks. Fortunately, word spread and a good number of students asked if they could join us and we ended up with about 10 students every morning for 3-4 weeks.

As part of the provision, we offered breakfast. Toast, specifically. Plate-loads of it - that the students never bothered with, so I ate a lot and so did my year 8 form!

It was really easy to run. We subscribe to Mathsbox.org.uk, so printed a booklet of their Skills Check worksheets. 2 pages from each of sets 1 to 6 at three different levels to suit the needs of the students that we'd invited.

Students came in, were handed theirs and worked through it - asking for help where they needed it and were directed to the same problem on the next sheet to check that they'd taken in what had just been said.

The question is... did it work?

Was it worth rushing in and being there from 7:30 because one student couldn't wait for 7:45?!

I'd like to think so.

Our data suggests so. The average progress made by all students in our Year 11 cohort last year between their second mock exam and their GCSE exam was 0.2 grades. Using the 11 students who achieved for at least a full week, the average progress in the same amount of time 0.4.

Will we be doing this again this year? Absolutely.

We're running it two mornings per week from the first week back after half term - 30 students have been invited with students already asking why they haven't been invited ("It's not that you're not welcome, you definitely are, but we haven't identified a need to tell you that you need to be there.")

I'm hoping two mornings per week is more sustainable over a longer period of time to maintain engagement and progress. It also gives me the opportunity to identify different needs throughout the year.

Friday, 26 October 2018

Dear Primary School Teachers

This year, I've been working hard.

I get up, I walk the dog, I get ready for work, I go to work, I work from 7.15am until 4pm with few breaks, head home, feed, bath and bed our little one, and then do more work.

I feel broken. Physically and mentally broken.

This isn't the purpose of my blog post.

This year, as part of my new role, I've been a part of more meetings. I was told in one of them that 'SATs are a formal examination process, not sat in rows in a hall, but definitely in exam conditions'.

Good, I thought.

I met a primary colleague at the same meeting who told me that they'd expect, in a standard class in one of our typical feeder primaries, two-thirds of their students to be able to add and subtract mixed numbers competently at the end of year six (having taught them 'tricks', as he put it).

Bad, I thought.

I've done a lot of work with our SOL this year, and my year 7 class is a good test of how well it will work. They all scored around 100 as their scaled score, which I understand to mean that they've succeeded on the year 6 curriculum set out by the DFE. For these students, that means we start year 7 building on this 'secure' knowledge.

They've performed well in class, on their low stakes quizzes and on their delayed homework. But on their first 'proper' assessment, they've done better on the things taught in class than the things they supposedly succeeded with last year.

3 years ago I taught a year 11 class which had a girl called KC. I asked how she was working at a grade E after getting a 5 in her SATs - "my teacher gave me the answers".

Nonsense, I thought.

"No, she didn't", I said. Her friend chimed in - "No, sir. She did. She gave me the answers too. All of us."

Oh no, I thought.

SATs are a formal assessment? That certainly doesn't sound like it.

Taught tricks to be able to do things? That's hardly building understanding or being helpful for assimilating information.

I spoke to my year 7 class today. I talked about KC and I talked about yesterday's assessment and how this was how assessments are to be done - in silence, without help. A test of their independent understanding. I asked them if their SATs experience was similar to the assessment yesterday, and only 5 said yes. I rephrased my question - "Put your hand up if you had an adult help you in your maths SATs at the end of last year". 24 out of 24.

Oh no, I thought.

I understand that primary schools need to have as many students pass as possible. I understand that this is a high stakes environment, but so is secondary school.

I don't care about our school targets. Students achieve what they achieve. I care about our students.

Students are set targets for the end of year 11 and their progress mapped towards this from day one - using their prior attainment. If students have inflated prior attainment and this is used to map progress, these students are not, and likely never will be, on the trajectory that they need to be on from day one and all we'll do is tell them that they're underachieving for five years.

As a student of Craig Barton said, "It's hard to have a growth mindset if I keep doing shit in tests, Sir."

For the sake of our young people, their motivation, their mental health and their understanding, stop helping students in their SATs.

Allow them to achieve at their level, so that the expectation of them isn't too high when they leave your school for the last time and they have 5 years of progress, rather than underachievement.

It's unfair and our young people deserve better.

I get up, I walk the dog, I get ready for work, I go to work, I work from 7.15am until 4pm with few breaks, head home, feed, bath and bed our little one, and then do more work.

I feel broken. Physically and mentally broken.

This isn't the purpose of my blog post.

This year, as part of my new role, I've been a part of more meetings. I was told in one of them that 'SATs are a formal examination process, not sat in rows in a hall, but definitely in exam conditions'.

Good, I thought.

I met a primary colleague at the same meeting who told me that they'd expect, in a standard class in one of our typical feeder primaries, two-thirds of their students to be able to add and subtract mixed numbers competently at the end of year six (having taught them 'tricks', as he put it).

Bad, I thought.

I've done a lot of work with our SOL this year, and my year 7 class is a good test of how well it will work. They all scored around 100 as their scaled score, which I understand to mean that they've succeeded on the year 6 curriculum set out by the DFE. For these students, that means we start year 7 building on this 'secure' knowledge.

They've performed well in class, on their low stakes quizzes and on their delayed homework. But on their first 'proper' assessment, they've done better on the things taught in class than the things they supposedly succeeded with last year.

3 years ago I taught a year 11 class which had a girl called KC. I asked how she was working at a grade E after getting a 5 in her SATs - "my teacher gave me the answers".

Nonsense, I thought.

"No, she didn't", I said. Her friend chimed in - "No, sir. She did. She gave me the answers too. All of us."

Oh no, I thought.

SATs are a formal assessment? That certainly doesn't sound like it.

Taught tricks to be able to do things? That's hardly building understanding or being helpful for assimilating information.

I spoke to my year 7 class today. I talked about KC and I talked about yesterday's assessment and how this was how assessments are to be done - in silence, without help. A test of their independent understanding. I asked them if their SATs experience was similar to the assessment yesterday, and only 5 said yes. I rephrased my question - "Put your hand up if you had an adult help you in your maths SATs at the end of last year". 24 out of 24.

Oh no, I thought.

I understand that primary schools need to have as many students pass as possible. I understand that this is a high stakes environment, but so is secondary school.

I don't care about our school targets. Students achieve what they achieve. I care about our students.

Students are set targets for the end of year 11 and their progress mapped towards this from day one - using their prior attainment. If students have inflated prior attainment and this is used to map progress, these students are not, and likely never will be, on the trajectory that they need to be on from day one and all we'll do is tell them that they're underachieving for five years.

As a student of Craig Barton said, "It's hard to have a growth mindset if I keep doing shit in tests, Sir."

For the sake of our young people, their motivation, their mental health and their understanding, stop helping students in their SATs.

Allow them to achieve at their level, so that the expectation of them isn't too high when they leave your school for the last time and they have 5 years of progress, rather than underachievement.

It's unfair and our young people deserve better.

Sunday, 24 June 2018

Exam Experience

The higher-foundation debate has gone on for years. This is my tenth year of teaching and it predates me.

Do I enter borderline kids for higher? Is foundation better for them? This felt like a massive decision with the new GCSE last year, but I hope that this never makes a difference.

Being a 'higher' student is a bit of a badge of honour at our school. The notion that someone perceived to be a higher student might be entered for foundation sends shockwaves through friendship groups and rumours spread like wildfire - like someone's seriously ill... 'Did you hear about Jenny? She might be sitting foundation' 'Sir, is it true that Billy won't be doing higher?'

I never really had much of a concern about it. In my eyes, a grade 5 student stands an equal chance on either tier and a grade C student stood the same chance too. My mind was changed last year.

Meet Annie. Annie is a sixteen year old girl who can do maths. She can get by and she's in set 2. March comes around and she gets 40 marks out of 300. I made a decision - foundation. I knew she could do maths and I knew she could do the questions on the first half of those papers. What I didn't consider was that she could only do them with a run up - that she needed 15 easier questions to build up her confidence. Annie needed to be entered for the foundation tier for her GCSE.

It worked. Annie got a 5. A 5 that she wouldn't have achieved on the higher tier. She probably had a better exam experience too. She didn't toil for 4 and a half hours in the hope of scraping 30% together. This has changed my mind on the foundation-higher debate.

It has also changed my mind on how we should assess students from years 7 to 11. On how we can try to support every student's individual needs even in assessments. This is part of a longer journey for me and our department.

In terms of which tier to enter students for? Foundation for all until you prove yourself.

'Everyone does a foundation paper at the end of year 9. Get a 5, I'll let you have a crack at higher, because if you're not going to get a 6, then I doubt you should be entered for the higher GCSE.

I'd rather you felt smart for 4 and a half hours at the end of an 11 year journey than feel like all that hard work ultimately made you feel less able because you couldn't access 70% of a paper.' That's what I'll tell the kids.

Do I enter borderline kids for higher? Is foundation better for them? This felt like a massive decision with the new GCSE last year, but I hope that this never makes a difference.

Being a 'higher' student is a bit of a badge of honour at our school. The notion that someone perceived to be a higher student might be entered for foundation sends shockwaves through friendship groups and rumours spread like wildfire - like someone's seriously ill... 'Did you hear about Jenny? She might be sitting foundation' 'Sir, is it true that Billy won't be doing higher?'

I never really had much of a concern about it. In my eyes, a grade 5 student stands an equal chance on either tier and a grade C student stood the same chance too. My mind was changed last year.

Meet Annie. Annie is a sixteen year old girl who can do maths. She can get by and she's in set 2. March comes around and she gets 40 marks out of 300. I made a decision - foundation. I knew she could do maths and I knew she could do the questions on the first half of those papers. What I didn't consider was that she could only do them with a run up - that she needed 15 easier questions to build up her confidence. Annie needed to be entered for the foundation tier for her GCSE.

It worked. Annie got a 5. A 5 that she wouldn't have achieved on the higher tier. She probably had a better exam experience too. She didn't toil for 4 and a half hours in the hope of scraping 30% together. This has changed my mind on the foundation-higher debate.

It has also changed my mind on how we should assess students from years 7 to 11. On how we can try to support every student's individual needs even in assessments. This is part of a longer journey for me and our department.

In terms of which tier to enter students for? Foundation for all until you prove yourself.

'Everyone does a foundation paper at the end of year 9. Get a 5, I'll let you have a crack at higher, because if you're not going to get a 6, then I doubt you should be entered for the higher GCSE.

I'd rather you felt smart for 4 and a half hours at the end of an 11 year journey than feel like all that hard work ultimately made you feel less able because you couldn't access 70% of a paper.' That's what I'll tell the kids.

x

Friday, 19 January 2018

Successes

Our first day with students every year is called 'Target Setting Day'. It's an opportunity for form tutors to meet with students and parents about their current situation and to talk about their needs for the coming year and set some basic targets for them to work towards. To review this, we then have 'Progress Review Day' where we meet again and look for positives and share some more targets. Yesterday was one of those days.

I've spent a decent proportion of my time lately considering successes, after reading blogs, listening to a podcast or reading it in a book (I forget which) and totally redesigning our half-termly assessment procedures to suit that.

On Monday, year 9 students had an assembly on social responsibility. At break time I had a duty in the dining hall - 400 students and me, it seemed like! After most had made their way to their next lesson, one student (M) had stayed behind to put other people's rubbish away, put the chairs that students had moved back and show a bit of social responsibility. I thanked him, profusely, and went on to my next lesson too, thinking little more of it.

The next day, I went to see a colleague after a lesson to hear him speaking to M about how he needs to change his ways if he's going to be a success at our school or he should find another - a far cry from the student I saw approximately 23 hours and 40 minutes ago.

I made a point of going to his form tutor the next morning, sharing Monday with him and passing on a golden ticket (our reward for doing something above and beyond). I was told he needed this, as there's not a lot going for him at the moment. I ran into him period 1 and M thanked me for his golden ticket, so I patted him on the shoulder, said 'no bother' and made my way to do some work.

Yesterday, I was between appointments and took a walk around the sports hall where we were meeting with parents and students. As I walked towards a colleague for a chat, M headed towards me with his dad. Proud as punch, he turned to his dad and said 'Dad, this is Mr Taylor. He's the one who gave me a golden ticket'. I shook his hand, explained the circumstance, told him he deserved it and made my excuses as I saw another of my form with their parents ready for an appointment.

'He's the one who...'. One. Had M only had one golden ticket this year? Ever? I give out 30 or so a week.

It seems that this small act on my part made a huge impact on this 13-14 year old boy, and I hope it might spark a fire.

There's another kid in not so recent times I'll share too. S, her name was. Never in her class due to behaviour and arguments, our HOD decided to move her to my group so that she'd at least be in a classroom for the last few months of year 11. 'Just babysit her - she won't do anything for you'. That was right, for 3 lessons. Then she did some work. A lesson later she asked for help with something. Within a week or two she was at after school revision and leading class discussions. At her leavers assembly she sought me out, hugged me and through floods of tears thanked me for what I'd done for her. Her March mock was an F, then she came to me. Her GCSE result was a C. I class that as one of my greatest victories.

In staff training last week we had to write a piece promoting the importance of maintaining a positive mindset in our subjects. The crux of mine was that positivity breeds success, which in turn fuels positivity... And repeat.

Imagine not having that positivity. You struggled at primary school, or you're new to the country from some war-torn country. You know a few tables, can add, but struggle with the concept of division or subtracting double digits. You're anxious about your new school and you need a success, but your first assessment is hard and you get 7/60. The positivity isn't there and you can't fuel a success. Before you know it, you've done three assessments, scored 30/180 and you're underachieving. Imagine trying to break that pattern. I've never had to. I imagine it's true that neither have you. Ultimately, this is a significant proportion of our students and I think that with the new GCSE, now more than ever, it's so important that we find the successes for students to fuel their positivity and more successes as we work through our 5 year journey.

I get a little scared thinking about those 7/60 students and what this must do to them. I get a little scared, so I'm trying to do something about it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)